As I was furiously working on my Emotional Mecha Jam game Orbital Paladin Melchior Y the other week, the tenth anniversary of my first GameMaker-made release, About a Ball, whizzed by without my notice.

So I’ve now been working in GameMaker and GameMaker Studio for over a decade. Before I purchased a license for GameMaker version 7, I hadn’t touched game design since 2003, when I collaborated with WiL Whitlark on the 24 Hours of ZZT game AdversiTurtle (I’d cut my game-making teeth in ZZT starting in 1997). My intervening six years had been devoted to filmmaking, having worked on over a dozen comedy shorts in some capacity with my collaborators at Bombdotcom Productions. In early 2009, I was wrapping up post-production on the feature film comedy I directed and co-wrote with Enoch Allred, Legends of Minigolf: The Flamingo’s Challenge. Somewhat to my own surprise, when I imagined my next creative project, I found my mind wandering back to video games and thinking I had some ideas about the intersection of narrative and gameplay (perhaps of interest is that one of the first projects I imagined was a Persona 3-influenced, visual novel-style adaptation of my own film Legends of Minigolf: The Flamingo’s Challenge)

I was reading a lot of anna anthropy’s articles about level design and was inspired by both her use of GameMaker in the creation of games like Mighty Jill Off . Not really sure where to start, I found a multi-stage tutorial Derek Yu had written on the TigSource forums walking the reader through the creation of a simple scrolling shoot-‘em-up. I followed along, creating a small shmup starring a space lion fighting black blobs. I improvised some power ups and other features and started to feel comfortable with how things worked under GameMaker’s hood.

My game-making ambitions were vague (outside of some way-beyond-my-scope blockbuster-budgeted pipe dreams), but I knew I had long wanted to develop a game like Zelda II: The Adventure of Link but with a stronger narrative and emotional component. I’d definitely have to learn how to make a platformer.

I downloaded a few sample platformer templates for GameMaker, but the kinds of coding I saw other people using didn’t mesh with what I’d come to understand about object interaction and movement from Yu’s tutorial. I was also still drawing lot of my programming intuition from my teenage experiences with ZZT. So, instead, I took the GML (GameMaker Language) scripting I’d learned from my lion shmup, and painstakingly fumbled through the basics of jumping and movement (note that half of my ZZT output was made up of various types of platformers).

I downloaded a few sample platformer templates for GameMaker, but the kinds of coding I saw other people using didn’t mesh with what I’d come to understand about object interaction and movement from Yu’s tutorial. I was also still drawing lot of my programming intuition from my teenage experiences with ZZT. So, instead, I took the GML (GameMaker Language) scripting I’d learned from my lion shmup, and painstakingly fumbled through the basics of jumping and movement (note that half of my ZZT output was made up of various types of platformers).

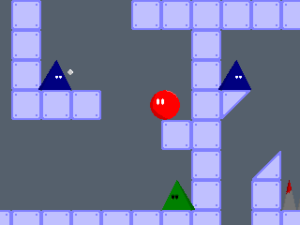

It’s cliché, of course, for amateur game-makers to hastily draw shapes (especially circles and squares) as the placeholder objects in their experiments, but I happened to add eyes to mine and began to think of it as a little character in its own right. Its enemies naturally became different, more angular shapes with crueler eyes. My experiments with collision, obstacles, and movement led me to crafting a small series of passages for the ball to traverse, and soon I found that I’d created a small network of rooms that folded in on themselves. I was making a game that I thought was actually kind of fun. I started implementing some of the ideas about level design I’d been meditating on, including the idea of the player’s goal being visible from the very first screen of the game.

About a Ball (a more or less meaningless pun on About a Boy, a title befitting an episode of a Saturday morning cartoon) is a brutal game. It took me a couple dozen tries to beat it again this morning, despite its short length. The version I have here is actually an updated and revised edition from 2012. Its original incarnation was even more brutal, with only five lives to lose before it forcibly kicked you out of the game (completely unnecessary, since the only progress that carries over from life to life is tripped switches and blood-stained spikes).

About a Ball (a more or less meaningless pun on About a Boy, a title befitting an episode of a Saturday morning cartoon) is a brutal game. It took me a couple dozen tries to beat it again this morning, despite its short length. The version I have here is actually an updated and revised edition from 2012. Its original incarnation was even more brutal, with only five lives to lose before it forcibly kicked you out of the game (completely unnecessary, since the only progress that carries over from life to life is tripped switches and blood-stained spikes).

It has a fixed, awkward jump with no gradations and no variability (there’s no sense of gravity, as you fall and jump at the exact same rate in each frame, in much the same way as my old ZZT platformers, and you don’t hover at the peak of your jump). However, the game’s sole stage is designed around this limitation. There’s no real story to speak of here. From the moment your red ball appears in the industrial warehouse-esque environment, the player only knows they have to make their way to the Lemmings-esque portal on the other side of the starting chamber’s wall.

The game has an absolutely opaque, inscrutable scoring system based on time spent and (maybe?) lives lost. My score from my most recent completion was 62,682. I can’t tell you what that means. It would’ve been higher if I’d taken less time.

The game has an absolutely opaque, inscrutable scoring system based on time spent and (maybe?) lives lost. My score from my most recent completion was 62,682. I can’t tell you what that means. It would’ve been higher if I’d taken less time.

At any rate, About a Ball was released to my blog on February 13, 2009. This was before GameJolt and itch.io provided a good place to house free game releases, so it was almost certainly entirely played by people in my social circle. I wouldn’t complete another game until 2010’s Pirate Kart entry Watch Ducks, even though I did attempt a handful of narrative platformer ideas with scopes way beyond what I was ready for. My experience mucking around with the interactions between About a Ball’s platforming mechanics soon led to a half decade of focusing almost entirely on tongue-in-cheek riffs on game clichés like the scoring system in Watch Ducks or wholly mechanical explorations of tweaks on the basic grammar of platforming games like Bulb Boy and ExpandoScape, mostly developed for quickie Glorious Trainwrecks events.

In this time, “narrative” (in its most conventional definition) in my game design work was mostly explored as a humorous framing device or an ironic counterpoint to a game’s mechanics. For my more mechanical experiments I was very into an idea of games inherently possessing narrative so long as they were running—if a player avatar progresses from the starting post to the goal post, a narrative has been expressed, even if it lacks traditional representational ideas. So into this concept was I that in 2012, when I released Caverns of Khron, I left out any contextualizing text within the body of the game itself and when I approached my friend Jane Allred to write a backstory for the game’s manual, I gave it the header of merely “A Story”—its own text fairly vague, but intended to allow the player to project whatever they saw in the adventures of a purple-haired adventurer’s sword-aided descent through increasingly bizarre screens purely derived from the interaction of objects on screen.

In this time, “narrative” (in its most conventional definition) in my game design work was mostly explored as a humorous framing device or an ironic counterpoint to a game’s mechanics. For my more mechanical experiments I was very into an idea of games inherently possessing narrative so long as they were running—if a player avatar progresses from the starting post to the goal post, a narrative has been expressed, even if it lacks traditional representational ideas. So into this concept was I that in 2012, when I released Caverns of Khron, I left out any contextualizing text within the body of the game itself and when I approached my friend Jane Allred to write a backstory for the game’s manual, I gave it the header of merely “A Story”—its own text fairly vague, but intended to allow the player to project whatever they saw in the adventures of a purple-haired adventurer’s sword-aided descent through increasingly bizarre screens purely derived from the interaction of objects on screen.

Only in the last couple years have I started to get back to exploring the richer narrative concepts that drew me back to game design a decade ago and resulted in the narrative-light About a Ball: Knight Moves, Liz & Laz, Nibblin’, and Monster Hug all have integrated story sequences. Further, while Temple of the Wumpus leaves a lot unsaid, it is a game all about reading and studying hundreds of bits of text to guide your avatar through a spiritual journey to which I want the player to bring a certain amount of their own experience (and, by no mere coincidence, is my most direct riff on Zelda II to date). Orbital Paladin Melchior Y fuses the action shooting genre with a visual novel format. What’s more is that I’m doing all of this in GameMaker Studio, having moved beyond awkward jumps and minor tutorial variations to scripting an entire visual novel system that integrates with a shmup. Having written my first visual novel, I’m eager to continue to explore what can be done at the intersection of my focus on mechanics and level design and the power of story.