Koi Puncher

I created the original Koi Puncher in 2012 as one of the 25 games I made in a two-week period and submitted to Glorious Trainwrecks’s Pirate Kart V event. The game was made in four hours, from start to finish. The title came from an email conversation I had with siblings Jared Allred and Jane Allred, who have a nephew who actually punched an actual koi (which, for the record, I do not endorse—please treat koi with respect and absolutely do not punch them).

I created the original Koi Puncher in 2012 as one of the 25 games I made in a two-week period and submitted to Glorious Trainwrecks’s Pirate Kart V event. The game was made in four hours, from start to finish. The title came from an email conversation I had with siblings Jared Allred and Jane Allred, who have a nephew who actually punched an actual koi (which, for the record, I do not endorse—please treat koi with respect and absolutely do not punch them).

When I sat down to make Koi Puncher, the title was all I had.

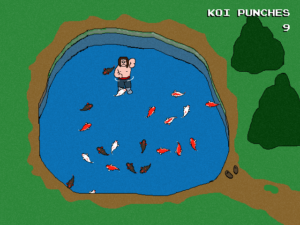

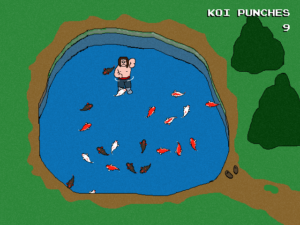

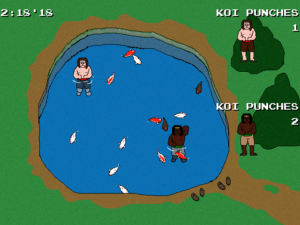

Koi Puncher is very simple. Terribly simple. Almost everything about Koi Puncher is there in the title. You play a koi puncher (here imagined as a burly, shirtless white dude giving off mild Conan vibes). The koi puncher swims in a pond and punches koi. To leave the game, your koi puncher leaves the pond. That’s it. That’s the game.

That initial installment was made in four hours. Koi Puncher MMXVIII was made in four months.

And not just four months of leisurely programming, either. I spent more nights than not staying up way past my normal bedtime, Saturdays spent hunched over my desktop, trying to refine and polish a game that still boasts an intentionally low-fi, hand-drawn, amateurish vibe.

2018

Near the end of 2017, I committed myself to making a new version of Koi Puncher. The game had been a hit at some local game dev showcase events at Shoryuken League in Eugene, Oregon, and I can credit Brit and Cullen at doinksoft for encouraging me to revisit it and give it a little extra pizzazz.

I’d toyed with the idea of revisiting the game before. Despite its spontaneous, hurried creation, I was really satisfied with the way the game felt. The way the koi moved and the player character animated were weighty and comical.

There were two main things I wanted to add: multiplayer functions and koi genetics. I’ll get to the latter in a minute.

But I really had no idea what I was getting myself into. I thought I’d be spending a few weeks on it. Weeks became months, from the very beginning of January to the 20th of April.

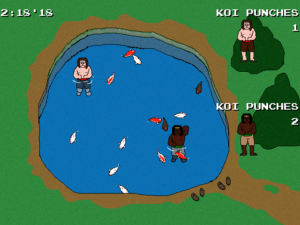

In the same two-week game-making blitz that gave birth to Koi Puncher, I also made a quickie multiplayer version I called Koi Puncher: Championship Edition. While the first game was about punching koi at your leisure until you had your fill, Championship Edition gave you a second player (a palette-swapped, dark-skinned Luigi to the original player character’s Mario) to compete against for two minutes. In a sense, I felt that was a betrayal of the original game’s spirit, but I was testing the waters.

In the same two-week game-making blitz that gave birth to Koi Puncher, I also made a quickie multiplayer version I called Koi Puncher: Championship Edition. While the first game was about punching koi at your leisure until you had your fill, Championship Edition gave you a second player (a palette-swapped, dark-skinned Luigi to the original player character’s Mario) to compete against for two minutes. In a sense, I felt that was a betrayal of the original game’s spirit, but I was testing the waters.

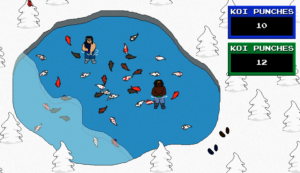

I wanted MMXVIII to retain the focus on pure koi-punching, but I quickly realized that with up to four players, it’d be fun to include versus modes like the Championship Edition. This, in turn, also led me to creating single-player score attack modes and, later, challenge minigames. So while I keep the pure koi punching experience at the game’s center, it becomes a small activity center with a multitude of game modes, for both solo players and groups of friends. I wanted Koi Puncher MMXVIII to work as a party game.

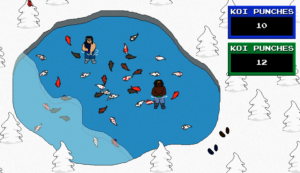

I decided I wanted to let players choose from a roster of thinly sketched characters. There are ten playable characters in all (eight available at the start, two unlockable) to choose from. I also wanted to support four players with as few as two gamepads and as many as four. I vastly underestimated how complex that would be. Coding all of this was a whole new level of challenge. I learned a lot about programming in GameMaker Studio.

Koi Genetics

In the original Koi Puncher, when two koi with the same body markings—out of a set of four—run into each other, a new koi can spawn. To keep this from going too overboard, I gave them invisible breeding buffer timers and sex distinctions, so reproduction would only happen if a koi of sex “1” met a koi of sex “2.” This very small idea about invisible characteristics got stuck in my head, and back in 2012 I had begun to think about a game called Koi Breeder, a simulation game where the player would select koi for breeding, each of which would have a long list of genetic characteristics invisible to the player. There would be dominant and recessive genes that would influence color, markings, fin shape, and more. I never quite figured out how I wanted the game itself to work beyond the genetic idea, so I shelved it, but never quite stopped thinking about it.

So Koi Breeder fused with Koi Puncher. Each fish in the game has a handful of genes, and the way they appear is based on how those genes are programmed to express. I never did well with biology (fun fact: I have a recurring theme in my nightmares where I’m failing the biology class I am retaking and can’t graduate from college), but my high school-level, oversimplistic understanding of gene expression led me to a place where I can fake it well enough.

Mutations can happen, too, leading to the possibility of extremely rare koi colors, patterns, and body shapes. Ultimately, there are thousands of possible koi that can be found in the game.

Mutations can happen, too, leading to the possibility of extremely rare koi colors, patterns, and body shapes. Ultimately, there are thousands of possible koi that can be found in the game.

So eager was I to tackle this koi genetics idea, it was actually the first programming and design task I set for myself. It was fairly simple to draw the various possibilities of body colors and patterns (which are dynamically created from a handful of component sprites), but getting inheritance to work the way I wanted took a long-ass time. I can’t exactly remember, but at least the first six weeks was primarily devoted to tweaking everything about koi genes (and I’d continue to fiddle with it throughout production).

Most play sessions will not last long enough to see some of the weirder combinations that come through breeding (selective breeding is somewhat possible if unruly, since koi will disappear after three hits, removing them from the gene pool). So to allow players to create a permanent reserve of prize koi they could develop over time, I created the “home” pond mode, letting players keep their favorite koi.

The dynamics of koi inheritance, though, is completely aesthetic, affecting absolutely nothing about the core game. Most players could probably play MMXVIII without ever noticing the genetics, let alone fathom what was going on under the hood. This, honestly, is still my favorite part of the game and one of my favorite things I’ve ever done creatively, largely due to its surface frivolity.

Life

The last few weeks of development on Koi Puncher MMXVIII had very little to do with punching koi. The five new ponds I’d created were surrounded by a lot of empty grass and dirt that I’d sparsely populated with trees and shrubs. It was empty, in contrast to all the liveliness in the pond.

Suddenly, it occurred to me to add cats.

Suddenly, it occurred to me to add cats.

Initially, there was going to be one cat. A tuxedo cat modeled on the two lovely cats in my house, Boris and Natasha. It would appear on rare occasions, sit at the edge of the pond watching fish, and run away when a player character got near.

But why stop with one cat? Why not take that same cat sprite, recolor it, and make, like, half a dozen cats?

So I did just that. Different cats live at different ponds. They sometimes curl up and take naps. But is that all there is in this world? Koi and cats?

Then I made birds. Different kinds of birds. And turtles. And even a peacock that appears under very special conditions. They all have their own behaviors. And then I even added little interactions between them. Suddenly, the world around the weird little ponds of Koi Puncher was bustling with life, little ecosystems.

Koi appear in Temple of the Wumpus

Again, this has nothing to do with punching koi. All of this is completely independent of the mechanics of what the player is doing. The games I make have long featured animals (Watch Ducks, Owl Forest, Ungrateful Birds, to name a few), and this new use of wildlife unlocked something in me that I’m continuing to explore in the games I’ve made since (Temple of the Wumpus, primarily) and am working on now.

Wrapping Up Koi Puncher MMXVIII

There’s more that I could go on about at length here. Programming and balancing the challenge minigames was fun and rewarding. Creating the game’s unlockables (something I’ve liked to do in my “bigger” games, like Caverns of Khron and Explobers), consisting of two player characters and two maps, caused me to scrap and rewrite some of the game’s core organizational structure. The game also has some really deep-cut references to Caverns of Khron, which has led to more metareferentiality in the games I’ve made since (for example, the original koi puncher character makes a cameo in my remake of Aaargh! Condor).

Koi Puncher MMXVIII is absurd on a number of levels. It’s a ridiculously simple, almost aimless concept that functions almost identically to games I spent no more than six total hours developing, but I spent four months reworking and expanding it, adding in fidgety little things around the edges. I wouldn’t have expected it, but it’s somehow become one of my favorite, most personal games.

A year after its release, I’m releasing a small update to Koi Puncher MMXVIII, bringing it to version 1.1. It fixes a bug in the ice stage and makes it less likely that you’ll run out of koi in a multiplayer game (koi now have more hit points in those modes). If you haven’t given it a shot, I hope you’ll step into my bizarre, koi-punching world.

And please, again, don’t punch real koi.

____________________________________________

This post was cross-posted at itch.io.